Investigative journalism has, from a very early stage, exposed cases where automated systems were clearly problematic. One of the most notable examples is ProPublica’s “Machine Bias” investigation. In 2016, the U.S.-based nonprofit newsroom published a report on a computer program used nationwide to predict future criminals. Their findings revealed that the program was biased against Black individuals. According to ProPublica’s analysis, the algorithm that powered the prediction program “was particularly likely to falsely flag black defendants as future criminals, wrongly labeling them this way at almost twice the rate as white defendants.” It also mislabeled white defendants as low risk “more often than black defendants.”

This story was published a year after OpenAI was founded, when artificial intelligence was still a niche term and ChatGPT did not even exist. Nearly a decade later, people now depend on AI-powered chatbots for everything from planning family vacations to creating personalized training plans, as well as more sensitive tasks for which generative AI may not be ideally suited, such as offering psychological advice… Or speeding up recruitment processes.

OpenAI has announced that it is working on a hiring platform to match companies with talent. Meanwhile, many companies already use their ubiquitous chatbot to screen hundreds of resumés in minutes. However, this might not be a good idea: Bloomberg reported last year that it can result in racial discrimination.

Investigating bias in AI

While some may argue that AI systems are not worse than humans, these tools have two features that make them potentially more dangerous: First, it’s still unclear how they generate their results under the hood, even when they seem to transparently show how they reached their outputs. Second, they are now accessible to almost everyone.

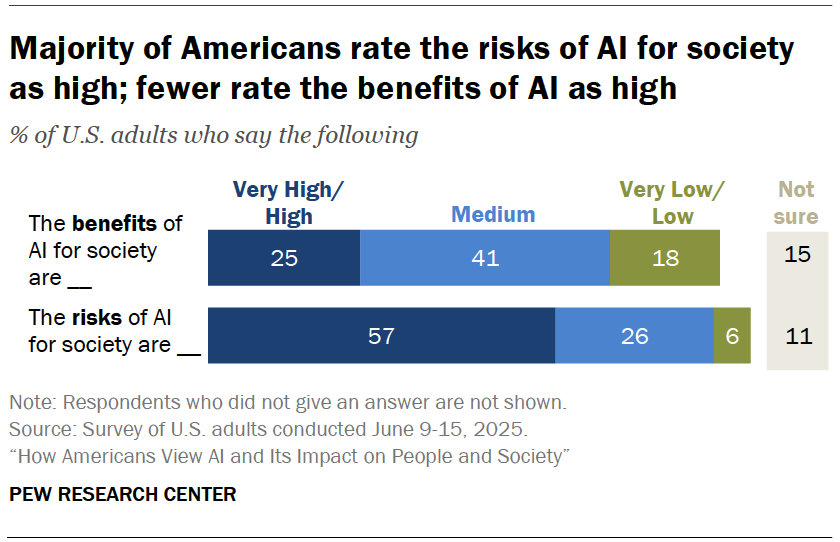

Journalists must therefore question how these systems generate outputs, but this responsibility should not rest solely with specialized tech reporters. According to a Pew Research Center survey in the U.S., most citizens view the societal risks of AI as high, and an even greater proportion believes understanding AI is important for the public.

So, where to start investigating bias in AI?

“Garbage in, garbage out” (GIGO) —or “rubbish in, rubbish out” (RIRO)— is a common saying in computer science. It summarizes the concept that flawed or poor-quality input produces equally flawed output. In artificial intelligence, this means that if the data used to train algorithms is biased, the results will also be biased.

Since the quality of the training data is a primary concern, let’s start there.

Training data contains variables—measurable traits or quantities, such as age, eye color, height, and marital status. The first step in analysis should be to check whether the AI system employs potentially unfair variables, like race or gender.

The use of such sensitive data, also known as protected attributes, might seem like an obvious red flag and may therefore be avoided. However, other variables may appear more objective or neutral but can still conceal bias. Postcodes are a classic example of so-called proxy variables for race or ethnicity.

Real-life examples with real-life impacts

Such bias was embedded in the fraud detection algorithm deployed by the city of Rotterdam, as revealed by an investigation from Lighthouse Reports and Wired. This algorithm, built by consulting firm Accenture, was praised as a «sophisticated data-driven approach» meant to serve as a model for other cities. But in 2021, the city suspended use of the system following a critical external review commissioned by the Dutch government. Lighthouse Reports and Wired had access to both the algorithm and its training data. The journalists found that, although the system does not explicitly include race, ethnicity, or place of birth among the 315 variables it uses to calculate a risk score, there are Dutch language requirements for receiving welfare that can serve as a proxy for ethnicity.

Sometimes, issues can be hidden deeper down in the training data. In 2018, big tech giant Amazon scrapped a secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women, as Reuters exposed. According to the reporters, the company’s recruitment models were trained to vet applicants by analyzing patterns in resumes submitted to the company over 10 years. Because most were from men in a typically male-dominated industry, the tool “penalized resumes that included the word ‘women’s,’ as in ‘women’s chess club captain’.»

AI-based tools are frequently marketed as more objective and efficient than humans. However, these systems are only as reliable as the data they are trained on, among other factors. For journalists, it’s crucial to recognize how the quality and use of this data can mask systems that perpetuate injustice and discrimination.

If your newsroom would like to learn more about investigating AI bias in your community, feel free to reach out! I am happy to discuss the best approach to meet your specific needs.